SUMMARY

The present late-modern times of globalization under the rule of the market pose new, traumatic forms of exile resulting from the ruins of national identities, of millions of people fleeing their countries and crossing borders in either legal or illegal ways, of walls raised to prevent entrance of travelers coming from an economic and cultural post modernity which is dividing the world into lands of labor and lands of misery and death. Modernity brought along a profound sign of exile, caused by political, social, and spiritual uprooting, by the decentering of native times, spaces, and regions that gradually faded away. This modern kind of uprooting was posited in the 18th Century by J.J. Rousseau in his novel Julia y la Nueva Heloisa. Still, if we go back to the origins of Western civilization, the Aegean world inflicted the penalty of exile as a most serious punishment, and looked upon exiles as living dead. In Euripides' tragedy Medea, the protagonist exemplifies heinous exile within a play that outlines various instances of exile. Coming back to modernity, it is then when we shall find literary, poetic, and philosophic exposures of the infinite varieties of the loss of a sense of belonging, personal inscriptions, the homes of the soul, all of them sorrows that may or may not entail geographic or non geographic violence. Modern subjectivity felt exiled from language, from individual marks, from the words that named the world, and from the very sense that identified life. This exiled subjectivity composed the modern esthetic symphony: to be a stranger in one's own homeland; to be a foreigner to filiation. In the realm of history, 19th and 20th Century capitalism found, in exile, the new foundation of a vast part of America through substantial throngs of migrants who had been forced out of Europe for economic, political, racial, and cultural reasons.

The loss of one's own

Nicolás Casullo

Translated by Marta Ines Merajver

Translation from Sociedad, Buenos Aires, no.25, 2006.

I

Nowadays exile would appear to be in extinction in the face of the logic presented by a way of life that can fit anywhere in the world, at any moment and in any space occupied by homogeneized urban populations. Still, by contrast, exile also appears as a belated awareness of a decisive condition that denounces an insomniac I, a real, unreal, or imaginary subjectivity; it is not important which. The world market redesigned the planet through an undifferentiated logic of regions that offer employment, regions for investment, extinct continents, and crossers of sea and land frontiers.

Like yet another vicissitude of an excessively Protean present, the remainders of native places and the ruins of identity crisscross the political and military upsurge of new walls, electrified fences, and armor-plated boundaries built to separate and define territories whose economic, cultural, racial, and religious marks are protected with unprecedented belligerency.

If something is to be learnt from news programs blaring from the TV screens in thousands of urban rooms on an ordinary day, it is that we have reached the end of the comprehensive, primeval, classic history that man used to find in his distinctive national codes, with his gods and his past; in other words, the evidence that there were communities that could not be replaced and whose loss was unthinkable. Or that losing them meant being subjected to the ultimate punishment.

Together with this present, where regions dissolve into the industrial, modern post-society, where virtual appearances and esthetic forms have taken the place (have taken our place) of an already “unnecessary” real world, it is patently unquestionable from every informative image, or from the scores of events we live through, that man's different lands and customs controls are impassable. Lands of winners, and lands of losers. Beautiful lands, and devastated lands. Lands protected by the law, lands of crime, lands of good, and lands of evil that only yield the imaginaries of social and national banishment; the brutal capitalist exiles.

If modernity, as a historical era beset with supposedly secularized desires and anguish, was warned of something, it was that the nodal experience of the free spirit, of the glittering invention of a reached I would imply the unavoidable loss of everything it had fleetingly accumulated as property. This loss took on the appearance of fate as determined by the end of religious terrors, by the demythifying illustrated explanation, and by the melancholy that was now found in the background of all essays on critical thought, aroused by the novelties of the Western world. Still, the fate that uprooted belonging with a forcefulness that pertained to no-one and for which no-one was to blame –it was simply the echo of a “new age” –became a proof, esthetically and existentialistically sought, a desired experience of remoteness, of banishment, and of disencounters; the Baudelairean myth as, confronted with the question about his homeland, the poet answered: “I do not know under what latitude it lies”.

II

One of the first instances of literary awareness of modernity as a form of exile is found in Jean Jacques Rousseau's protagonist of Julia y la nueva Heloísa: this was a conscience that simultaneously discovered its sovereignty and self-estrangement. Written in 1761, almost at the dawn of Encyclopedism in the arts and sciences, and a year before the Contrato Social, Saint-Preux, the protagonist, elatedly rises from the letters to his beloved, teeming with illicit deeds mixed with guilt, and masterly guided by Jean Jacque's pen. His journey to Paris from the town where he spent his childhood and early youth is an 18th Century version of Ulysses, with a newly-minted heroicity that anticipates how the depths of the world had withdrawn to the innermost parts of the subject in conflict; to the private seething of his own representation, amid idealizations and sleepwalking.

Thus, the geography of exile shifts into the self. In the wild imaginary , the outside may appear under whatever outline or silhouette. To Saint-Preux, everything will amount to “exile”, where he stands unprotected: “I am a wanderer, deprived of land and family”; “my days go by like unending nights”. Leaving one's self behind and despairing to know what one has evolved into, standing on the unfathomable threshold of drifting, amounts to a perception or guiding star where the modern pilgrim of feelings came to life. He who wanders from place to place wrapped in a nomad's cloak, following an itinerary that will eventually lead him to his own face in a mirror –a place that is not to be found– rather than roaming among regions and landscapes to be found outside. To the protagonist, the insalubrious quality of his Paris home will provide the evidence of definitive expatriation from genuine affects. Ironic characters and beautiful souls gush forth.

Now the mystery lies in the yearning for a world filled with profound sensibilities which, phantasmatically, has “remained behind” for good. Or else the loss of this world turns it into a mystery to modern subjectivity, which will no longer be able to say what it – ‘it' standing for both the world and the self –was like. One hundred years before Baudelaire, and in the same city of lights, Saint-Preux says, “I am alone amid the crowd”. Stripped from his soul, the young man tells us. In a place where words and reality do not match, as he used to believe. “I am right in regarding the crowd as a desert”. And this is bound to be the first journey of a refugee to whom no night shelter will open its doors: the notion of a depleted world in spite of its tumultuous novelty of languages, truths, sorts, and strife. Exile from the soul is the experience of the desert in the city. What is full is in fact empty, will conclude soon afterwards German poet Jean Paul, longing for a living Christ. Expatriation in the desert does not need geographies or corresponding Biblical myths. Now the youth knows that the same happens in Paris, Rome, or London. He tells his beloved about it, and the I that tells the story firmly grounds all its forcefulness as an exile and a lover.

Now everything is as impossible as it is possible. To return; to possess. The desert is a frame of mind and also a ghost. A crossing. The journey toward the border. It is the place that delays the finding of a new, modern homeland, a space of successive mirages with no appointed spaces. “I spend the whole day in the world,” says Saint-Preux. This is ostracism in the big city, the distant, barren land, no man's land: the world that remained. The metropolis will bring together a vast dispersion of the ancient worlds in a ghostly, mercantile World that can be culturally groped for, but that slips between our fingers like sand. Still, at the same time, it will become a stage where Saint-Preux will begin “to feel the intoxication of this life”. Delusion, appearance, prejudice, concealment, mask, hypocrisy, rhetoric, insensibility, “terrible loneliness and bleak silence” are the relentless glares of a sun that scorches the barren land and offers the opportunity of delirium, trembling, fever, going blind with the light and the steep shadows. The desert, the non-homeland, is a mixed habitat which, while instituting the modern imaginary of some lost native soil, of a yesterday where it is impossible to seek refuge, also injects the fortitude of grief: that of expatriation as a sweet pain of what was thought of as a possession. Therefore, exile in the sphere of the filiar, the amicable, the desired.

III

If we go back to the beginnings of communal order; namely, to those of the wars, the law, and the foundation of politics through acknowledgement of conflict, living in alien lands has always been permeated by the sorrow that forced this step and by the grieving imposed by estrangement. The Greeks deemed this kind of punishment as second to death only; to a great extent, it meant just another form of dying while watching their own corpse immersed in the misfortunes of life.

Perhaps the toughest, most ruthless document of confinement in foreign geographies is to be found in Euripides' Medea, where the wretched, fearful wrath experienced by the protagonist is a narrative inscribed within a wider story: that of a time of exile which, through impending revenge, affects everyone involved. She had arrived as a “fugitive”; she was “a stone from the seas” lying on the shores, the strip of land forever hit by ocean waves, in an indistinct place which, 2500 years later, Dutch filmmaker Lars Von Trier would set in a waterland, a spot that neither admits of marks nor records traces of any kind. To the poet of the ancient Aegean, this was the place where she could only mourn for “her father, her land, and her home”, gone for ever.

According to the tragedian, Medea learns the misfortune of dwelling away from her homeland. But her exile, that piles her past crimes upon her head, is worsened by the threat of a new forced departure. Creonte, king of Corinth, orders that she “be banished” from the territory at which she had arrived with her children, while her husband Jason, the cause of her misfortunes, agrees that “exile involves many evils”, and admits that he was driven to commit the crime of marrying Creonte's daughter to escape further exile. He, too, feels uneasy in foreign lands.

Existence might be taken to stand for a tragic series of exiles that bury previous exiles. Accordingly, the chorus poses the primary question that pervades the story of spiteful Medea with inexpressible horror: “which is the land where you will find salvation?”, echoed by her own answer expressed by another eternal question: “which city will have me?”. Medea's question does not refer only to the political decision of a power that menaces and banishes. In Euripides' poetics, exile is the world as perceived from the very place the subject is. It is “that which is hated by the eyes” and which demands that “the alien adapt to the ways of the city”. Exile is the impossibility to re-view, to re-connoitre, to re-place. In the first and last place, it is the impossible to re-present. Medea has been exiled from the representations that should set her life in order: she has been estranged from happiness, from the conjugal bed, from love, from her children, from her own gender –she confesses that she would rather be a man and a warrior than a child-bearing mother.

Medea mourns her ostracism. Jason fears yet another exile. Creonte protects himself by banishing what he feels as a threat. From the horizons of tragic art, Greek culture depicts the sorrows of uprooting as the type of politics that barbarizes the victim's existence, as a naturalized history lurking in the shadows, lying in wait. The culture of the inhabitants of the ancient Aegean lacked a modern subjectivist spiritualism that could have turned the exiled part of conscience into a construction or derivative of another world –secret and torn, perhaps –within the world. Instead, in the Hellenic universe it becomes a part of nature in its pure state within a universe that assigns a fate. The distances have been erased between the wandering fate –via the gods, knowledge, or stigmatized heritage –and the bearer of evil. But the very figure of the one who has been condemned to being uprooted, or of the one who finds a living death in being uprooted, is symptomatic of a land that philosophizes, of an esthetic land that wonders about what is native to it as well as about what is foreign. A land that wonders about estrangement in a strangely determined manner. A land that Socratically carries its own knowledge to the edge of estrangement. The misfortune that pulls us away from happiness composes rhetorical geneses, and politically unthinkable notions, while a Greek stormy sky looms large as a possible hamartia in the way of what will become victimized.

IV

It could be posited that the great initial issue of a seed of thought lies in the indifference of cosmos, of an absurd outside that cannot be encompassed. The desertion that outlines man's fate refers to the sense of all senses, to a lack of sense, to a reckoning of what is missing, to what is mute, or to the unknown language that places us in the world. It is the first estrangement as a location for what will later be defined as a creature: the condition of humanity. This location precedes every relation to and explanation of the world, and this situation pathetically requires that all of them be produced. A later step, always lagging behind the rising sun.

If Sense in fact exists, it will always surpass us; it will never reach us and stay. Or else it may be a totalizing vector, like fire, brushing through the heavens, through divinity. Regardless of which it is, we have been banned from its trajectory. Exiled from sense, the only thing left to us is an endless journey in which we dream to allay the pain of being outsiders to a land that existed before and will exist afterward, identical to itself in its estrangement: we will not be there.

Therefore, what really matters and completes the silhouette –the material quality of the ‘self'-is the uncanny, the unspeakable, an other language. The world. The outside. Then our own silhouette is outside itself –exiled from itself –because what pertains to it fails to contain it, and it does not inherently contain what we call sense either, something that supposedly lies outside thought, in the surrounding world, in the transcendental, in “social life”, in what the huge human tribe will later name history.

We are indebted to the archaic poetry produced by goatherds for an initial consciousness of the only universe that conveyed meaning in the chronicle of mankind: the meaning of gods that were also makers. That which is extraordinary and belongs to no-one. At the foot of the impressive, holy mountain, Hesiod was able to think of the trilogy that then shaped and composed mankind; i.e., the notions of ‘present', ‘past', and ‘truth'. Poetry. These notions did not come from the inapprehensible world of the heavenly gods, but turned out to be the essential, brittle, linguistic means to comprehend that which banishes us from fate: we were thus able to understand the whys and wherefores of life, death, and memory. Of the raging details and marks that come to us as a gift, a curse, fleetingness, or pain.

And thus it happened, according to the songs by the Greek aoidos: narratives rose from the amazement caused by what was ours/ by what we were, by discovering that we were strangers to the most important aspects of our selves. Hardly envisaging that which, through belonging, actually deprives, but in the context of a foggy sun, of a night moistened by thick vapors of dew given off by the Muses of Mt. Helicon, the poet sings. In other words: to be, among blurred images. Among images askew and iridescent, likes the ones that still persist, perhaps, after the first esthetic stroke, in a cinematographic flou that shows and conceals things.

What literature, caught unawares, first turned into song, was later on transformed into philosophy: man's expatriation from his own surroundings as the gesture that prologues all manner of thought. The possibility of posing questions from a position of amazement at the real, at man's innermost estrangement from the real. What was it all about? Well, it had to do with the riddle that made a man out of man; in other words, the obligation of having to understand all that was his, and to view the world as an intruder that takes on different shapes and undergoes transubstantiation. It was about the exhaustion resulting from wondering about what was his as if his constituents always lay outside, in ex-istence. As if, above anything else, life had always been intended to step out from the spiritual silhouette where life dwells into the kind of confinement that has always demanded that consciousness gaze into a foreign land.

Exile on the land, then. And from such a perspective, the fateful condition implied in setting off from oneself toward an utopian one's self. Setting off toward an endless questioning about the region of the “human” condition, and making both the departure and the one-way journey into the most profound dimension of a pondering existence. An experience of exile that Western historical modernity consummated in the novel, its larger-than-life favorite poetics. From a fictional way of philosophizing –or philosophizing fiction –that could be woven only from representations of an I drowned in terror, free, released from its own jail-like discourses, recreating itself in kaleidoscopic parodies, and picturing the laughter of the gods. An I that discovered that the riddle was the initial fracture and distance between that other “I” and the world; between the word and the cloaks of the real, with the purpose of translating distance and ostracism in post-epic terms, tragic or satirical, destroying literature insofar as it was the ultimate form of accounting for the lack of homeland and home. According to María Zambrano's philosophy, it was about acknowledging the night of history thinking of the experience of exile which, in her view, is a time that resembles that of dreams, away from history, from days, and from groping hands.

V

Still, María Zambrano speaks of an exile which, like black shadows, will pervade political, economic, social, and cultural modernity when 19th and 20th Century history unravels its violent economic exploitation, revolutionary utopias, barricades, independence exploits, popular communes, totalitarianisms, and warfare at home and abroad. Society had become a projectual construction, implacable and possible from the standpoint of the philosophies of history: just as the Romantics had predicted, there was more financial power, more political engineering, more mythologies, added to the actions implemented by the masses organized as trade unions, political parties, armies, or the nation itself rising up in arms. It would not be possible to think of this dimension of exile –the countless exiles of thousands of people brutally banished by the expansion of world capitalism –without contextualizing the experience of forced migration within the plexus of modern Argentinean historiography.

A scattered, lonely colony in the insignificant Viceroyalty of the Río de La Plata, the outlet for Peruvian silver and, basically, a seat of smugglers, after the revolution and the ensuing independence the country's architecture was built on the basis of massive exile from Europe, proving true what had initially been set down in Sarmiento's and Alberdi's chimerical writings, just as medieval utopists dreamt of an “unseemly” history turning into the history of a “golden” city. It was necessary for the country to stop looking like an Asian desert crossed by nomadic bands of belligerent gauchos (such was Sarmiento's disdainful description) and to grow into a welcoming territory for white 19th Century refugees. Two different ways of starting from those that were left at the other side of the fence.

In the 19th Century, reformulated by the millions of exiles coming from a millenary history, driven away from their homelands by a ruthless economic pressure translated into social barbarousness, cultural catastrophe, shattered existential identities, filiar smashing, beheaded memories, and linguistic orphanage, Argentina was restructured –whether as a fake Arcadia or as a place of undoubted commonal reparation –with expatriates in the leading roles as the new subaltern society reached certain regions of the country. Consequently, under such circumstances, history amounts to exile, and exile amounts to violence exerted against a background of tradition, a wealth of customs, idiosyncratic manners, physiognomic resemblances, phantasmatic imaginaries, silenced unconscious minds, and memories of things and people gone without the opportunity of being portrayed.

This final form of exile is identity as unthinkable, the kind of identity that cannot be replaced by either reflection or emotion. It is the biographical detail that challenges the quid of identity as nothing else does, and by identity I mean here the unspeakable phenomenon of life rather than the external symbols that it carries. An economic, political, religious, or racial chink irreparably splits singularity. The whole is cut asunder: the individual no longer is what he was, and neither is he what he has reached. He lives between two worlds, in an in-between that cannot be thought of as such; it can only be felt as a set of shadowy experiences that are difficult to name. María Zambrano speaks of Spanish exiles torn apart from their roots, scattered in various countries once the Spanish Civil War was won by Franco's faction. She speaks of ahistorical inhabitation, telling of a nightlike hiatus that engulfed the voices, the scents, and the well-known sky of the homeland, that same sky that German esthetic theorist Johan Winckelmann described as the parusia of a language, the mystery of art, the cultural mould that turns a woman into a particular woman and a man into a particular man.

As a punishment, exile steals away the circumstances of birth, childhood, youth, the native land in their most profound proofs of existence. The exile is an outcast from his community. The experience of he who has been deprived of his homeland is one that leads him to think of his homeland more than ever before. It is also under such circumstances that the questions about the immediate, the filiar, and the close acquire an authentic philosophic consistence without the intervention of either philosophers or philosophy. Yet modernity was polyphacetic, giving rise to national literatures as well as to openings that facilitated the escape of thousands of aesthetes who mistrusted the fate of their original latitudes. By the same token, it multiplied the dispersion of intellectuals and politicians fleeing defeat and persecution.

A one-way journey: Argentinean history throbs with a substratum composed of refounding exiles which show the national as a choice made by victims of punishment on their way to this country, to “the Southern Seas”. An accomplished journey. An itinerary which, from time to time, will continue to buzz at the gates of Consular buildings in the ghostly hope of a return ticket for a journey that might destroy the new foundations. It is typical of exile not to part with its structure of parenthetical time, in which perhaps Medea's grief might be soothed, or her crime might ultimately install a different narration. It is inherent to exile to pretend to block up the original stones with other ontologies snatched on the way. From there it always refers back to the question about the identity of things and references, as if it were what it in fact is not: an interval between dwellings. Instead, it becomes petreous in its inquiry into a bent destiny, for this is indeed the obsessive question that haunts exiles, that assaults women who are bearing their children far away.

The human condition? Adam's expulsion from Eden decided by a God that condemns his creature to move through history? A decentering of poetics that unveil the thin edge dividing language from the real? Perhaps a tangible chronicle of those who were prey to misery, to threats, and managed to survive? Many of those men beyond the frontiers, those who were deported, cast out, and forced to migrate, were endowed with a new kind of lucidity. It would seem as if straying away from the homeland uncovered a threshold to pry into secrets. Karl Marx tracing back the origins of capital from a London library. Julio Cortázar rebuilding a far country. In California, Theodor Adorno thinking of the worldwide industrial culture. In Chile, Sarmiento dissecting the frustrated revolution. Rimbaud, silent in Africa. In Paris, Walter Benjamin laying the foundations for the archeology of the contemporary, Witold Gombrowicz and his daily scribbling about Argentina's anagram. James Joyce in Trieste, writing the first chapters of Ulysses. On many occasions, the foreign quotation marks the equinox of man's pregnant land. Whichever way one looks at it, exile amounts to loss, to an unknown place where present, past, and future would seem to lose their function as clues to sense. It is, then, one of the hard experiences in which the question about the sense of life makes its presence felt.

VI

No doubt it is Romanticism, understood here as a para-esthetic creed, that hyperbolizes the notions of an unexchangeable homeland, of a childhood language that determines fate, of literary nationalities and, at the same time, as a complement to the movement that roots life, it hurls its arrow toward the antipodes, as if home, the hospitable pater, the ownership of the self, could be achieved successfully only through a breach of time, space, and tradition. Through the evils of exile. Through a melancholy tinge cast over what has been lost.

Seen thus, the quality of exile is profoundly romantic and modern. It sums up exiles of different tunes and dimensions. It brings together Jewish and Christian backgrounds, Greek modulations, idealisms of torn subjectivity and political subjectivities that will only agree to revolution, war, and patriotic feelings. From this cultural conglomerate of imaginaries, the romanticization of the world understood its reverse: extreme ostracism. Then, through bold policies, through literature about ill-fated loves, through anarchist and socialist militancy, it bore testimony to the geographies and to the exiled distances of the Ithacas where the anguished rovers yearn to return. Ever since the 19th Century, to die for the homeland became an obsessive idea that branched into different meanings, though it illustrates our point. To die for having lost it, because it is a place of no return, because it kills you, or to give your life for a military poetic figure that accounted for a land and for being forced to leave it. Exile is precisely the dead land that lives or that, romantically, buds to life in the experience of its death by desertion. To romanticize is to play at not discerning between the life/death pair that afflicts the migrant, the stranger, the foreigner, the expelled, the fugitive.

As the capitalist world became deromanticized and many of the clues to modernity began to fade, the figure of exile that invoked pagan, theological, rebel, fictional, and communist echoes turned into a dun sketch, integrated into modernist tradition and replaced, by the 21st Century, for more scientific readings that speak of migrating crowds in search of temporary employment in the framework of economies that at least pay wages. One could add: a rather hard postmodernity, with its masses always on the move and stripped of the old myths and legends of exile. In our times, economic, sociological, anthropological, and cultural studies deriving from field work speak more accurately of these new human swarms pent up in the outskirts of Madrid, Rome, Los Angeles, Chicago, or Buenos Aires, all of them heirs to an ancient story.

Bibliography

E.H. Carr. Los exiliados románticos. Bakunin, Herzen, Ogarev. Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 1969

Eurípides. “Medea”, in Tragedias. Volume 1. Editorial Gredos, Madrid, 1991.

J. J. Rousseau. Julia y la Nueva Heloisa. Editorial Futuro, Buenos Aires, 1946.

Nicolás Casullo. “La modernidad como destierro y la iluminación de los bordes: la inmigración europea en la Argentina”, inImágenes desconocidas: la modernidad en la encrucijada posmoderna. CLACSO, Buenos Aires, 1988.

Nicolás Casullo. “Tu cuerpo ahí, el alma allá”, en Tierra que anda: los escritores en el exilio. Editorial Ameghino, Buenos Aires, 1999.

Nicolás Casullo. “Exilio, mito y figura”, en Educación y alteridad: la figura del extranjero. Colección Ensayos y Experiencias. Joint publication by Noveduc and Fundación CEM, Buenos Aires, April 2003.

H. Meschonicc. Les Tours de Babel. Editorial TER, France, 1985.

Jean Luc Nancy. “La existencia exiliada”, in Archipiélago magazine, # 26-27. Barcelona, 1996.

Massino Cacciari. “Las paradojas del extranjero”, in Archipiélago magazine # 26-27. Barcelona, 1996.

© 2007 Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales

.

Search P-Spigot

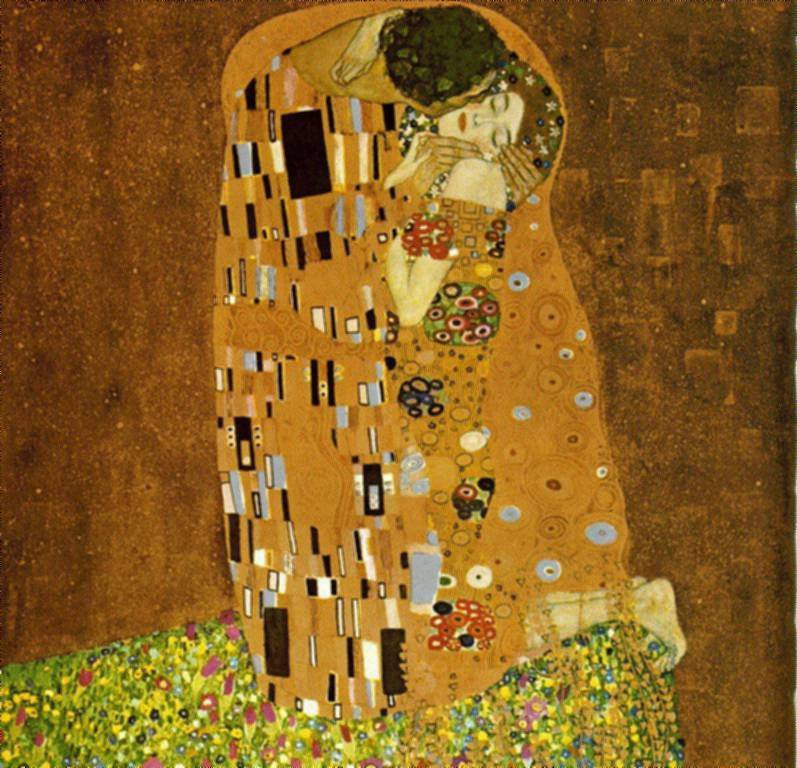

The great wave at Kanagawa.

This amazing work by K. Hokusai is one of my favourite works of art: vulnerability and strenght; the paradoxical beauty of imminent death and thousands of waves hidden in the foam -perfect example of the fractal nature of the Universe-.

The loss of one´s own, an article by Nicolás Casullo

Etiquetas:

La vida al revés. Life inside out

Publicado por

Sol

en

11:23

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Flickr username ♣ sol.ledesma

Flickr username ♣ sol.ledesma Myspace ♣polvoraspigot

Myspace ♣polvoraspigot YouTube username ♣ clavedelsol

YouTube username ♣ clavedelsol

1 comment:

Usually I do not despatch on blogs, but I would like to asseverate that this article really false me to do so! Thanks, indeed delicate article.

[IMG]http://www.sedonarapidweightloss.com/weightloss-diet/34/b/happy.gif[/IMG]

Post a Comment